I sort of feel like this movie just changed my life.

It may just be my regular afterglow from watching a movie I really loved. It may be my developing man crush on Steve Coogan, who appears to have a really fantastic taste in screenplays. But, I suspect the reason it got so much under my skin, is that it challenged my conception of grown-upness, by splitting its expression into the representation of two extremely different characters.

Without risk of spoilers, I hope, I think this film can be summarised as the story of a simple, trusting woman, exploited, abused, brainwashed and essentially enslaved by Catholicism in its various institutional and ideological guises, who remains (miraculously?) singularly unrepressed.

Alongside her, we have a world-weary writer. An affluent, successful career-man and intellectual, he is at little risk of himself being crushed under the steamroller of such blind and trusting faith. He is also very clearly basically a teenager.

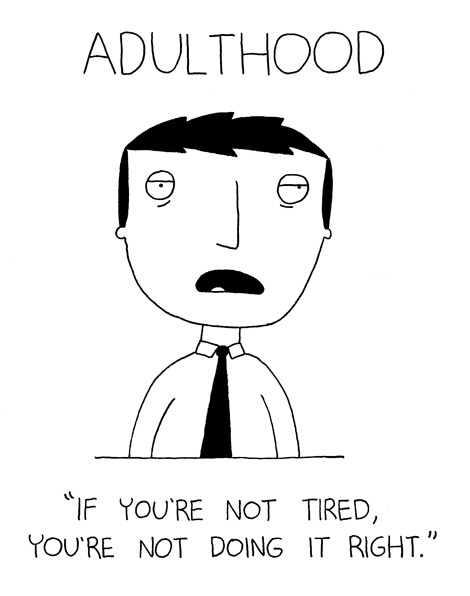

In the hope I can eventually tie all these strands together, I am reminded of this picture that every once in a while I see on facebook:

So which of these three options represents the real adulthood? And how come there are never any straightforwardly inspiring examples? It shouldn't really be worse than childhood or adolescence. Something good's supposed to happen on the way there too.

Here's what I think. Adulthood's about becoming a real person. No more adolescent, contrarian posturing or childish games of pretend. Grown-upness means taking responsibility for who and what you are. It also means accepting who you are no longer - which is to say, loss. Sometimes they can take away your baby. If you can somehow reconcile yourself to that, that probably means you're a real grown-up. I'm pretty sure I couldn't, the way I am at the moment.

Philomena seems authentic. It's a strange adjective to use, despite the fact that this is based on a true story, because movies and their characters can at the most be credible, but she distinctly feels like one of the most authentic people I've ever met despite the fact I've never met her. At the risk of sounding new-agey, she radiates love. Love of others and deep, accepting, love of herself. In a strange, paradoxical, very nearly incomprehensible way, I have to admit that there is something essentially religious about this self-acceptance. If you believe there is a God and this God loves you, that means you're objectively okay. That means you are completely free to be who you are.

But then, of course, there are the evil nuns. Evil nuns are all around us. Otherwise known as arseholes, they're there to exploit your vulnerabilities and weaknesses, and to try and persuade you, directly or through the threat they effectively represent, that you shouldn't be who you are because it's too dangerous. They have ruined religion. They have ruined self-love.

Evil nuns create embittered, frightened secularists like Steve Coogan's writer and myself. They make you wall yourself up to ensure freedom from their imposition, but then all you end up with is freedom to bang your head against a wall. You get stuck in perpetual rebellious adolescence because you can't get yourself to see beyond the fact that people are full of shit. Because you can't forgive.

I think this movie caused a little explosion in my brain when Philomena told Coogan's character that his righteous anger was pointless. Her exact words were "It must be exhausting." And it is. It genuinely boils my blood that you're expected to be perpetually tired in your adult life. I feel like somebody somewhere is trying to take away my baby. It maddens me that people judge you, on any pretext except that of potential harm to other people. I can't stomach it. I don't think I've ever really tried to.

Except I've been broken up with now. So maybe I'm beginning to.

No comments:

Post a Comment